To fully grasp the allure of the Peninsula, one need only follow the road toward Terranea. At the north entrance to the Palos Verdes Peninsula, the road is suddenly green—dwarfed on either side by massive banks of eucalyptus trees. In Malaga Cove the drive curves toward the sea, and the views open up and surprise … like a magician’s reveal.

The Olmsted Brothers, behind such American treasures as New York’s Central Park, paid close attention to circuit roads, climatic studies and nurseries on their projects. John Charles Olmsted and Fred Dawson, the original visionaries of the Peninsula landscape, began work in 1914 but were interrupted by the dawn of World War I.

The nursery they developed took root in the 1920s when hundreds of thousands of trees and shrubs were planted by Farnham B. Martin, including 10 varieties of eucalyptus. After John Charles Olmsted died in 1920, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. left Massachusetts to assume leadership of the plan for Palos Verdes Estates, retiring to the home built by Myron Hunt in 1925 on the bluffs of lower Malaga Cove.

The National Register of Historic Places cites Farnham Martin Park as “virtually unchanged” since Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. designed it. Carrying forth his father’s principles, Frederick made use of the existing sloped terrain and local material (Palos Verdes stone); he added the fountain as a formal feature. The stone terraces and dappled lawn, with gently curving paths framed by poplars and elms, lead to a pastoral landscape that invites people to gather within an elliptical perimeter.

The park grounds, adjacent to the Malaga Cove Library, represent New York’s Central Park fountain in miniature—a tribute to the versatility of the Olmsteds, whose portfolio includes more than 5,500 parks, arboretums, cities, cemeteries, college campuses, world’s fairs, private estates and residential communities. Landscape historian Christine Edstrom O’Hara calls Malaga Cove “the most complete example of the Olmsted Brothers’ regional approach to design in Southern California.”

Today a modest wood sign for “Olmsted Place” is barely visible under a pink Indian hawthorn bush, next to the flagpole in Malaga Cove, which is precisely the way Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. would have wanted it: “I have all my life been considering distant effects and always sacrificing immediate success and applause to that of the future.”

Beauty en Plein Air

The coastal road that runs from Malaga Cove in Palos Verdes Estates to Portuguese Bend is impossibly beautiful. Uplifted by the ocean and gauged by the surf around the time of the Ice Age, the ancient terraces appear upholstered in green and step broadly down to the sea. The peninsula’s gullies, canyons, cliffs and coves are teeming with wildlife.

“I paint because it’s going away.” – Thomas Redfield

All plein air artists are late, to crib from the Mad Hatter, for a very important date: with the sun. The 150-year-old tradition dating back to Claude Monet and other French landscape artists is about painting on-site to capture a vivid impression of the scene. What Monet did for his backyard in Giverny—or for haystacks, or for Rouen Cathedral—is precisely what the Portuguese Bend Artist Colony is doing the hundreds of times they paint open spaces on the Palos Verdes Peninsula.

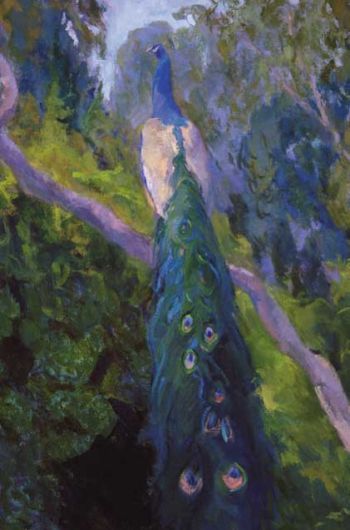

In Malatga Cove, where Amy Sidrane painted her Peacock (on display at the resort), two birds are stopping traffic with their haughty, unrushed strut. Off RAT (Right After Torrance) Beach, pelicans glide overhead and dive-bomb into the sea—another near miss for the dolphins, whose lacquered arches proceed rhythmically past The Neighborhood Church.

In Lunada Bay, where Richard Humphrey and Dan Pinkham—co-founders of the Portuguese Bend Artist Colony—went to school, the land opens up. Tart green lawns, fuchsia bougainvillea and massive Australian fig trees make way for hills carpeted in nasturtium, purple ice plants or, depending on the season, fields of mustard that fizz in Richard’s Above the Cove on a Spring Day or blaze in Stephen Mirich’s Almost Spring.

Along the western shore of this road, cliffs of every shape and color jut out to the sea. In The Cliffs and Sea at Point Vicente, Richard has captured this perpendicular majesty with his portrait of the lighthouse. In Insignificance Kevin Prince paints the light on the sea above the Point Vicente lighthouse with unblinking ferocity.

A Chapel with a Pedigree

Palos Verdes Drive continues south to the chapel that celebrates wayfarers—those pilgrims on life’s journey to a sacred place. Architect Lloyd Wright, son of renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright, drew his inspiration for Wayfarers Chapel from the redwood forests of northern California. Its trees, with soaring trunks and arching branches, form a natural cathedral that Lloyd sought to convey using glass and sky, trees and stone, sky and water—all with the 30- and 60-degree angles found in nature.

The Swedenborgian Church chose the Palos Verdes coast as the site for its memorial to Emanuel Swedenborg, the 18th-century Swedish philosopher and mystic who espoused tolerance and holistic living. With no permanent congregation, the Swedenborigian chapel was conceived to nourish and restore the wayfarer’s soul on life’s journey.

Helen Keller, a Swedenborgian since the age of 16, resonated with the church’s welcoming creed. “It makes me feel,” she writes, “as if I had been restored to equality with those who have all their faculties.”

This awakening was Helen’s spiritual equivalent to her breakthrough at the water pump with teacher Anne Sullivan. After six years of “dark, soundless imprisonment,” she writes, “that word ‘water’ dropped into my mind like the sun in a frozen winter world.”

Across the channel in Santa Catalina, the sailors call the chapel’s tower “God’s candle.” Lloyd named his architectural exclamation point the “Hallelujah” tower; it chimes on the hour, and its 16-bell carillon peals after

every wedding ceremony.

Writer in Residence

At Portuguese Point across Palos Verdes Drive South, the Harden Gatehouse—where Joan Didion and her husband, John Dunne, brought home their infant daughter, Quintana—is immortalized in The Year of Magical Thinking, a memoir in which, after the loss of her husband and then her daughter, she revisits the young family’s rental home by the sea.

“I experienced a sudden rush of memories: getting out of the car on that highway to open the gate so that John could drive through; watching the tide come in and float a car that was sitting on our beach to be shot for a commercial; sterilizing bottles for Quintana’s formula while the gamecock that lived on the property followed me companionably from window to window.”

The year was 1966. Joan had brought her adopted daughter home from St. John’s Hospital, having left New York City and famously rejected it in her 1967 essay for the Saturday Evening Post, “Farewell to the Enchanted City,” which became “Goodbye to All That” in her iconic collection of essays, Slouching Towards Bethlehem. The family would live in Palos Verdes briefly, then in Malibu, only to return to New York City.

In this poignant excerpt from her September 25, 2005 essay “After Life” in The New York Times Magazine, she again returned to memories of Palos Verdes, seeking reunion.

“In my unexamined mind there was always a point, John’s and my death, at which the tracks would converge for a final time. On the Internet I recently found aerial photographs of the house on the Palos Verdes Peninsula in which we had lived when we were first married, the house to which we had brought Quintana home from St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica and put her in her bassinet by the wisteria in the box garden.

The photographs, part of the California Coastal Records Project, the point of which was to document the entire California coastline, were hard to read conclusively, but the house as it had been when we lived in it appeared to be gone. The tower where the gate had been seemed intact but the rest of the structure looked unfamiliar. There seemed to be a swimming pool where the wisteria and box garden had been.

The area itself was identified as ‘Portuguese Bend Landslide.’ You could see the slumping of the hill where the slide had occurred. You could also see, at the base of the cliff on the point, the cave into which we used to swim when the tide was at exactly the right flow.

The swell of clear water. That was one way my two systems could have converged.”

Written by Fabienne Marsh