The modern poet John Masefield writes, “I must go down to the seas, again, for the … wild call … that may not be denied.” The term “ocean,” before the Europeans sailed “beyond the sunset,” referred to any water beyond the Strait of Gibraltar, which the Greeks called the Pillars of Hercules. The first ocean, named for the Greek Titan Atlas, became the roadway to the rest of the world.

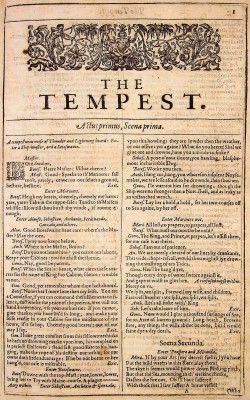

William Shakespeare sets his final play surrounded by the ocean. He titles it The Tempest, which denotes “sea storm” and then, ironically, creates his most tranquil atmosphere controlled by the magus Prospero.

In Italian, Prospero means “the favored one,” and magus is the singular form for the term magi, who are those “skilled in magic, astrology and wisdom.” Prospero’s world is characterized by a “strange drowsiness” that is “full of noises, sounds and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not.”

This “prosperic” ambience of controlled tranquility comes about because of Ariel, an obedient sprite, whose name is Arabic for “living God.” Prospero’s supernatural agent “comes with a thought” and carries out his vengeful plan to punish his enemies, who usurped his kingdom and set him adrift on a leaky boat along with his daughter, Miranda, to die in the ocean.

For Miranda, her 12-year oceanic experience has been an adventure into the wild. She survives an epiphany, which reveals her true royal identity, and her first encounter with teenage love. Her reaction to all of this is one of delight when she exclaims, “O wonder … O what a brave new world that has such people in it.”

These “such people” of Miranda’s brave new world, besides her magi-like father, include a drunkard, a fool, a half-beast/half-immortal creature, a remorseful king and father, two ambitious brothers who covet their brothers’ lives and fortunes, her father’s invisible servant and “the first” man she “ever sighed for.” These clowns, crooks and cronies are the typical people who inhabit Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. From his first comedic play through his thoughtfully evil and tragic dramas and into his historical portrayals of tyrants and benevolent kings, they have set the standard for character development and presentation for the past 400 years.

So what about this thing called the ocean? This wide expanse, seen from space, gives earth its bluish glow, which radiates an illusion of coolness in our solar system. Matthew Arnold, the 19th-century poet and teacher, writes that Shakespeare left “the loftiest hill and planted his steadfast footsteps in the sea.”

There is a renaissance portrait termed “the Chandos Shakespeare,” and if it is Shakespeare, he is wearing a gold earring. Today a gold earring is an adornment and fashion statement, but when the world was trying to discover all of its secret places, sailors depended upon the stars to guide their journeys. Then an earring was an amulet of good fortune—its circular design having neither a beginning nor an end.

It was the hope of the sailor who wore this talisman that his journey would end where it began. Was Shakespeare a sailor? Or was he an entertainer trying to control his own destiny? Both are possible.

There is a void of information concerning his premarital life, so the seafaring possibility does exist. His plays reveal, by their settings, that he had more than a cursory knowledge of the renaissance world, with a literary itinerary that includes Athens, Bohemia, Denmark, Illyria, Messina, Padua, Paris, Rome, Scotland, Spain, Troy, Tyre, Venice, Verona, Vienna and a never-named island that resembles Bermuda.

Bermuda, the mid-Atlantic apex of mystery and possible setting of his play The Tempest, provides a recapitulation of Shakespeare’s most successful plots and themes: absolute power that corrupts absolutely, sibling rivalry, love at first sight, love’s rocky road, lecherous deviancy, revenge at all costs, mortals acting foolishly and countless opportunities for self-reflection, soul-searching and the crossing of the fine line that separates the real from the fantastic. All of these complicate and intertwine themselves in The Tempest from beginning to end.

At one point, Shakespeare steps cautiously from behind his alter ego and reveals one of his most profound secrets that “we are such stuff as dreams are made on.”

The oceanic experience provides the opportunity for the discovery of the preciousness of dreams and echoes back to his play A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It’s as if the gold ring in that famous left ear defines the career of Shakespeare’s writing life.

As The Tempest ends, Prospero’s island has become a prison for all of his enemies. He proclaims, “My project gathers to a head.”

He is within a single action of accomplishing his revenge. His charms have “strongly” worked, and those who threatened him stand suspended in the mist of their own vulnerability. Powerless, they unwittingly await his wrath, but Prospero’s oceanic experience moves him in a different direction.

He listens to Ariel, that “living God,” who shares that if he were human his “affections would become tender.” Prospero pauses and then declares, “Mine shall.” He next delves into his “nobler reason” and proclaims, “The rarer action is in virtue than in vengeance.”

This last act of forgiveness releases and frees not only the criminal/sinner but the victim of the transgression. The audience hears and sees this when Shakespeare employs the ocean and its baptismal and restorative power. It’s only at the end of his career when this magus of the stage shares his most enlightening discovery: “Nothing of him doth fade/But doth suffer a sea change/Into something rich and strange.”

*All quotations except where noted are from William Shakespeare’s play The Tempest.

Written by James T. Cross

Update: Shakespeare By the Sea will present Cymbeline at Terranea Resort on August 18, 2016 at 7 p.m. For more information, visit shakespearebythesea.org.