Alex Gray was on the hunt for a very particular wave. The 29-year-old professional surfer from Palos Verdes lives to chase storms and far-flung swells in exotic locales, and earlier this year he had his sights set on Tahiti.

“I know going into April through August that there’s going to be at least one incredible swell that goes through Tahiti,” he says.

From age 12 to his early 20s, Alex was entirely focused on competing in professional surf events. “The day after high school, I jumped into the professional World Qualifying Series (WQS),” he says. “I traveled 10 months out of the year, and I was chasing points.”

His goal was to become one of the top competitive surfers in the world, and in his early 20s that goal was entirely tangible. At one point, he was ranked as the 49th surfer in the surfing world.

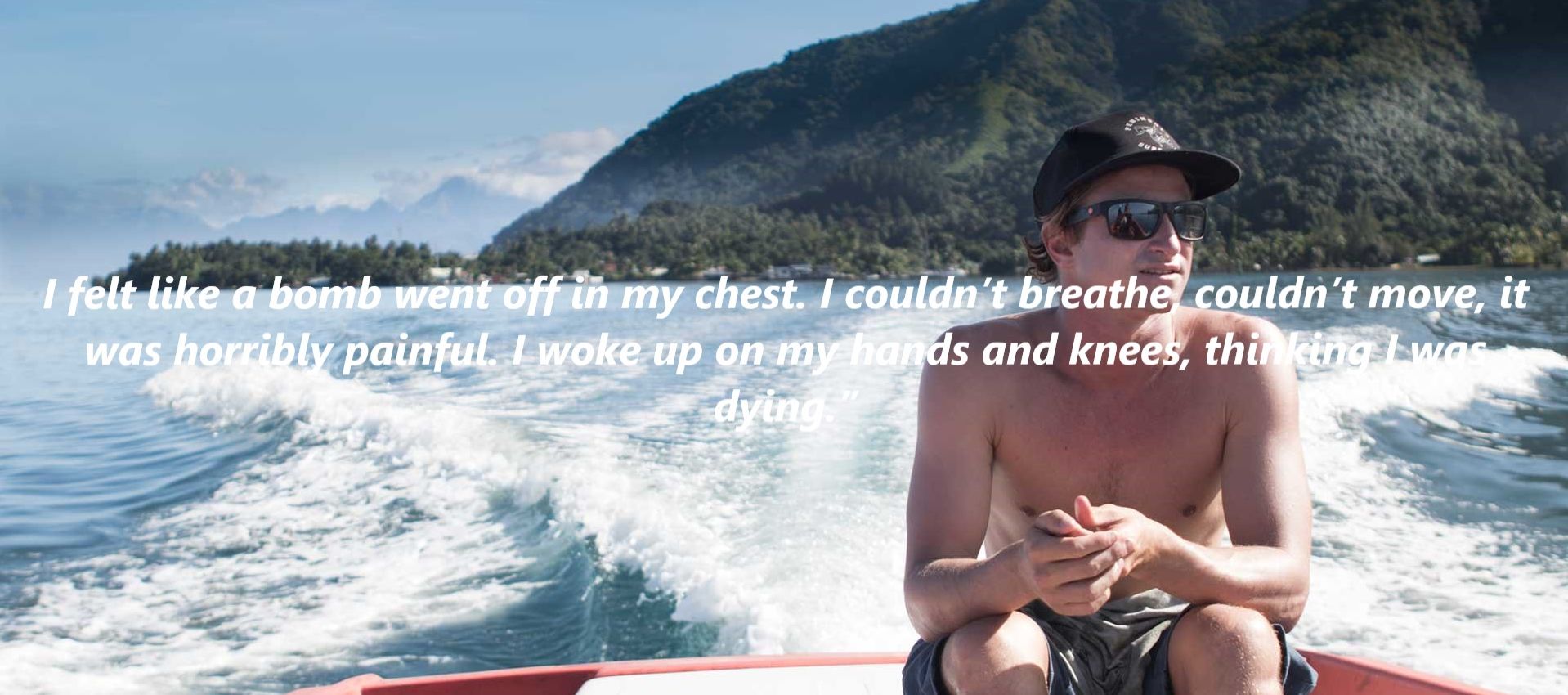

At 22, Alex was dealt a devastating blow. After returning home from a trip to Hawaii, he was diagnosed with pleurisy—an infection of the membranes that coat the lungs and chest. “I felt like a bomb went off in my chest. I couldn’t breathe, couldn’t move, it was horribly painful. I woke up on my hands and knees, thinking I was dying.”

Hours of surgery helped remove the build-up of fluid in his chest, but the recovery process kept him out of the water for months. And by the time he was finally ready to start competing again, Alex’s ranking had dropped dramatically—he went from 49th to somewhere around 1,000.

The news, he notes, was crushing. “My whole world changed, and my career stopped,” he says, adding that internal changes within the Association of Surfing Professionals (ASP), coupled with miscommunication, had been the cause for the drop in rank.

But with the support of his sponsors, Alex switched his game plan. The South Bay surfer focused less on “chasing points” and more on riding challenging, formidable waves across the world. “My goal now with surf travel is to go places where no one is surfing. It’s the best feeling when you’re with your best friends surfing with no one else around in some of the best waves-that’s why I started surfing,” he says.

His aim for Tahiti this year was straightforward: find that “perfect wave without anyone out.” Though that sounds simple enough, Alex is quick to point out that it’s a bit complicated to execute.

“The numbers [for this swell] weren’t oh-my-god-this-is-the-swell-of-the-year, but the conditions were amazing, and there wasn’t any wind,” he says. Data showed that Tahiti was going to be hit by a sizable swell; wind was going to be minimal, which meant wave quality would be exceptional.

But Alex was faced with a dilemma. He could go to one of the most popular breaks in Tahiti, Teahupoʻo (a world-class break that would be breaking exceptionally at the time but would most likely be crowded), or he could try a no-name, somewhat finicky spot nearby in Tahiti, where he could possibly grab his ideal wave completely on his own.

“I’d surfed it twice,” says Alex about the no-name right-hander, noting that both times ended with heavy wipeouts (including one that resulted in a fair amount of stitches). “But it’s a world-class wave, and it’s a place that no one surfs, and it’s twice as hard to get the correct conditions there.”

Alex decided to go for it. Following a whirlwind of last-minute logistics, Alex and professional photographer Bo Bridges headed to Tahiti for a three-day surf trip. “Everything has to come together, especially for a trip like this,” says Bo, a Manhattan Beach local whose professional experience includes everything from covering ESPN’s X Games to shooting talent for Rolling Stone and Sports Illustrated.

“We’re dependent on the weather forecast, the wave direction and the big one is the wind. You never know what [the conditions] will do. It can change while you’re on the plane,” he says.

A last-minute trip of this sort can be intensely difficult. “You torture yourself, your mind and body,” Alex says.

During the trip they were up at around 3:30 a.m., driving more than an hour through rural Tahiti and then hopping onto a boat. From sunup to sundown, Alex was in the water, searching for his wave, and Bo was standing by on a boat, camera in hand, waiting.

“We rode our patience pretty hard those days,” says Bo. There are physical risks, of course, when it comes to surfing waves with faces roughly 20 feet in height. The waves, for example, break over shallow, razor-sharp reefs.

And at the no-name spot, even Bo had his own dangers to deal with. Many of the big-wave spots in Tahiti have channels where a boat or Jet Ski team can idle and stand-by, safe from any incoming waves. But this spot didn’t have a channel, which meant the boat captain had to stay on his toes or risk taking a wave head on. “We were constantly grinding the engine to get out of the way of set waves,” says Bo.

There are professional risks involved too. After two days of less-than-stellar conditions, Alex was starting to get nervous. He notes that the “nuts and bolts” of the swell didn’t show right away. And they’d timed the trip so their second day was supposed to be the best, but the surf was less than stellar. He was afraid that they might miss the swell entirely.

“By the third day, I was tripping. The night before I didn’t sleep well at all,” Alex says. He notes that when it comes down to it, he’s willing to put himself on the line and risk passing up a decent, crowded break for an unknown spot that’s rarely surfed.

But he knows that his actions also impact those who support him—namely his sponsors and photographers like Bo. Volcom, he notes, was hungry for an image of Alex surfing a sizable wave on his own, and he needed to supply them and other sponsors with the content they wanted.

“I want Bo to get great images as well,” he says. “My lack of sleep doesn’t come from me; it comes from me involving other people and hoping that it works out for others as well,” he says.

On the third day, the air temp was hovering around the 90s, and the water was roughly in the 80s. The water was crystal clear. “From the boat you could see 200 feet below you,” Alex says. They weren’t expecting much for their last day, but the waves finally arrived.

After days of learning the ins and outs of no-name spot, learning how the waves broke and where he needed to take off, Alex finally scored his ideal wave—completely on his own. “I could see it moving along the reef, and I could tell it was bigger than anything that day,” he says.

“It might be the most perfect wave I’ve ever ridden,” he says, adding that the face of the wave was roughly 25 feet. All of the stress—that need to satisfy his sponsors and ensure that Bo got the shots he needed—fell away with that wave.

“It was the most perfect wave I’ve ever seen,” says Bo. “He nailed it. There was no one there except for us to capture it. Every drop of water was in its perfect place.”

Bo notes that, for him, a trip like this encapsulates his love of surf photography. Unlike shooting in a studio, “out there it can get hairy and tricky,” he says. One is never quite sure what to expect, and the ever-changing environment is simply thrilling to Bo.

Following that excellent wave on the final day, Alex and Bo began to head back in. But the surf was up that afternoon, completely empty and breaking flawlessly, and after two frustratingly meager days, Alex couldn’t help himself. He kept hopping off the boat and paddling back out.

Although Bo and the boat crew had spent most of the day roasting in the 90º weather, they stopped the boat and let Alex paddle out each time. Surfing, as Alex points out, brings him the most joy in life. Bo and the others knew they couldn’t stop him from jumping back in—not when they’d spent two days waiting for these superb conditions.

“For me, the addiction of surfing comes from being in the moment,” he says. “It’s a mindless reaction. It’s where I find myself living in the moment more than any other part of my life.”

Written by Stefan Slater

Photographed by Bo Bridges